Written By Christy Sherman Photography by Callie Beale Photography, The Ford Field and River Club, The Richmond Hill Historical Society and Worth Gaylor

The Winter Estate of Henry and Clara Ford

Henry Ford once said that “What we call waste is only surplus and surplus is only the starting point for new uses.” Perhaps this belief was instilled in Ford during his childhood as the son of a mid-western farmer during the late 1800s, when little was ever wasted. Ford later applied the principals of recycling to his personal life, manufacturing plants, and endeavors here in Richmond Hill. In the early 1920s, Ford began purchasing and restoring antebellum plantations in Ways Station (now Richmond Hill), some of which were situated on thousands of acres. Decades later, Henry Ford would find a new use for the abandoned rice fields—a place to experiment with rubber producing plants and other agricultural products for use in the automobile industry.

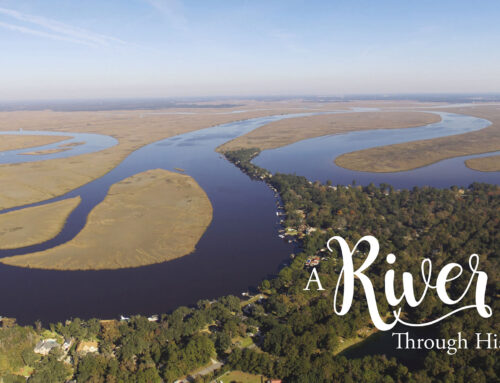

The Fords chose the site of a former rice plantation, Richmond-On-Ogeechee (formerly Dublin), for their new winter home; no surprise considering the beauty of the property. Three long, double rows of live oak trees formed the shape of an “H,” presumably planted by John Harn, who had received a 500-acre land grant from King George III in 1748. Frederick Law Olmsted, considered the “father of landscape architecture,” visited Richmond in 1853 after taking a wrong turn when trying to find nearby White Hall Plantation. He described Richmond as having “…rows of old live oak trees, their branches and twigs slightly hung with a delicate fringe of grey moss, and their dark, shining green foliage meeting and intermingling naturally but densely overhead… I stopped my horse, bowed my head, and held my breath. I have hardly in all my life seen anything so impressively grand and beautiful.”

When the Fords purchased the property over 70 years later, it must have seemed like the promenade of ancient oaks created paths to nowhere. The Richmond Plantation home had been destroyed by Federal troops on December 10, 1864, days before their attack on Fort McAllister. Still, the beauty of the site remained. Situated on a high bluff overlooking the Great Ogeechee River, the Richmond site provided abundant flora and fauna, wildlife, history, and the southern charm the Fords were looking for.

Nearby, another example of a bygone era, the Hermitage Plantation, was at the center of a debate between preservationists, the City of Savannah, and the Port Authority. Built in 1820 by Henry McAlpin on the Savannah River, Hermitage was best known for “Savannah grey” bricks. City officials accepted Henry Ford’s offer to purchase the mansion for $10,000 with the promise that he recreate it at the old Richmond Plantation. Brick by brick, or rather Savannah grey by Savannah grey, the Hermitage was dismantled. The mortar was carefully removed and the bricks were cleaned and transported approximately 20 miles to the Richmond site.

Meticulous planning went into every detail of their new southern mansion. Clara had a 1/12 scale model home with model furniture constructed to help with the process. With the help of prominent Savannah architect, Cletus W. Bergen, the 1820s Hermitage was reimagined and recreated to include all of the latest conveniences of the 1930s, including an elevator and commercial-grade stainless steel appliances. The 6,900-square-foot home called “Richmond Hill” included a drawing room, dining room, library, kitchen, six bedrooms plus a servant’s room, and seven bathrooms. Prominent elements such as the “Temple in the Winds” columns, colossal portico and a wide main central hall, which spanned the width of the home, were features the Fords maintained in an effort to reflect the Hermitage structure. The Fords also added elements of Federal and Georgian architecture, such as the Federal-inspired entrance door with leaded-glass fanlight. Views of the Ogeechee River were maximized and the home was designed to be light and airy, in contrast to their castle-like Fair Lane estate in Michigan.

Mrs. Ford enjoyed entertaining in her dining room, which was adorned with mural wallpaper depicting landscape and nature scenes. The room was furnished with an oriental rug, custom-scalloped shell corner china cabinets, and antique mahogany Philadelphia-style Chippendale furniture. The Fords often hosted dances on the lawn, bringing an orchestra from Michigan by train to accompany local students and teachers from the nearby Community House, a school built for teaching economics and dancing. The gatherings at Richmond Hill Plantation were understated and simple, unlike some of the fancier events hosted at the Dearborn residence. Dr. Leslie Long, who worked for the Fords for many years, wrote in his book The Ford Era at Richmond Hill, Georgia, “Mr. Ford did not care for elaborate things- just simple beauty.”

“Simple beauty” could also be found in the landscaping. Camellias, magnolias, azaleas, tea olives, dogwoods, and other southern flowers brought colorful life to the property. An ornate garden gate led to a prized rose garden. Gardeners planted winter-blooming annuals and bulbs for the Fords to enjoy when in residence.

Henry enjoyed his own special features of the estate including his daily walks to the yacht basin, built for his 28-foot cabin cruiser, Little Lulu, and oyster roasts at his very own custom oyster house. He converted the old rice mill on the property, heavily damaged by Federal troops during the Civil War, into a powerhouse. An old generator from a Ford Motor Company plant along with two V-8 motors, a steam engine, and steam boilers supplied steam heat, water, and electricity to the residence. Located in the upstairs room of the powerhouse was Henry’s personal laboratory, where he spent time working on watches, car parts, and various other mechanisms. Getting to and from this personal hobby room was easy. An 1100-foot underground tunnel, which housed utility pipes from the powerhouse to the residence, was accessible by the elevator from either floor of the home. Mark Heppner, Vice President for Historic Resources for the Historic Ford Estates in Michigan, says Ford built a similar tunnel at Fair Lane. “There is a long tunnel (about 400-500 ft) from the main residence to the powerhouse. Although certainly convenient for access in bad weather, its main function was for underground utilities. Just like in Richmond Hill, Henry had an experimental laboratory on the top floor of the powerhouse here in Michigan, where he often tinkered and worked on big projects.”

Although the Fords called Richmond Hill their home away from home for almost 25 years, they would enjoy the Richmond Hill house itself for only 11 short years. Henry Ford passed away April 7, 1947, days after returning to Dearborn from Richmond Hill. After Clara’s death in 1950, the Richmond Hill estate and approximately 70,000 acres—which included Fort McAllister, community buildings, residential neighborhoods, and plantations—were sold to International Paper Company for $5 million. Employee houses and community buildings were sold to those who could buy them. Fort McAllister was given to the state of Georgia, which is now a Georgia State Historic Site. International Paper retained much of the land for timbering.

Richmond Hill Plantation would see many changes in the years following the Fords’ last visit. The property changed ownership several times and was unoccupied for many years. In 1959, the house and 1,200 acres were purchased by an industrialist from New Hampshire, Gilbert Verney, who sold it after his wife died to Mr. and Mrs. James McCook of Macon. Mr. McCook died a year later in 1960. The next year, his widow sold the property to four eager investors from Glynn County, who intended to make it a resort. Kenneth Rogers interviewed one of the investors, Algie Outlaw, for the Atlanta Journal Constitution Magazine in April 1964: “We have 475 acres of reclaimed rice land and we already have a contract for growing a winery,” Mr. Outlaw said. “Ford grew a lot of experimental things… we’ve found things in the woods he set out, including huckleberry bushes and rubber trees… you should have seen how this place had grown up when we got it. We started clearing out underbrush in the woods several months before the sale was completed.” The investors also had plans to build an 18-hole golf course, a yacht club, and to convert the home to an inn and clubhouse. “For horseback riding we’ve got the most beautiful trails you can imagine on the dikes—a good 15 miles of them…Ford’s old laboratory will be our golf shop. The players will start and wind up there for both nines.” As it turned out, Mr. Outlaw and the other investors were a little ahead of their time. Their plans fell through, and in 1969, Richmond Hill Plantation would again go up for sale with an uncertain fate.

By the mid-seventies, Ford’s Richmond Hill Plantation was in deplorable condition. According to a nomination form for the National Register of Historic Places, “Bees were boring into the columns, the leaded-glass windows were broken in many places, and the house was open to the elements and vandals. Clogged roof gutters have caused noticeable damage to ceilings and walls; and the humidity has caused all of the wallpaper to leave the walls, including the scenic wallpaper in the dining room.” At that time, the property was owned by George P. Tobler, an insurance underwriter from Long Island, NY. His plan was to restore the mansion as a community center and develop two golf courses on the grounds, one of which was to be the Ladies Professional Golf Association’s (LPGA) home course starting in 1975. Ford historian David Lewis visited Richmond Hill Plantation in 1973 and described what he found for Cars & Parts Magazine, “Rehabilitation of the mansion will come none too soon, for the structure, with woodwork rotting and doors askew, is in a state of considerable disrepair. Repairs and painting are much needed to restore the mansion to its former state of beauty. Ford’s laboratory, a former rice mill in which the first Ford-Ferguson tractor was assembled, has been similarly neglected. The walls of the once-beautiful garden have crumbled. The garden itself, like the grounds around it, is overgrown with weeds.”

Local resident Dan Collins remembers that time, “The rumor was that the mansion and course would be the home of the LPGA. During the early stages of the course development, a worker was killed in an accident out there that shut the operation down. A developer/investor (A.G. Proctor Co.) from St. Simons bought the property and turned the mansion into a restaurant.” Though short-lived, the restaurant brought new life to the old Ford mansion.

The 1980s brought a new decade of change. This time, it was Saudi Arabian businessman Ghaith Pharaon who was enchanted by the “beauty, splendor and serenity” of Richmond Hill Plantation, then on the National Register of Historic Places. In 1981, Pharaon purchased the partially restored home and accompanying 1,800 acres. He began an extensive restoration of the home, which included replacing over 500 windowpanes, refurbishing the wood floors, and returning the Savannah Grey bricks to their former glory. He also replaced the broad wooden steps leading to the entrance of the home with marble. But Pharaon made the most dramatic changes to the grounds and facade of the estate. In the book The View From Sterling Bluff, author Glenn McCaskey described some of the additions: “On the river side of the house, a large pool with a black bottom to reflect the sky had been added. In the center of the pool stands Gazzeri’s 1860 marble sculpture of ‘The Lovers.’ In the front, a pair of large, ornamental iron gates rescued from a New Orleans mansion has been installed to give a sense of entry. Gardens with life-size statuary and fountains have been created. Stables for Arabian stallions and Argentinian Polo ponies were installed.” Despite not a golfer himself, Pharaon was the one to finally create the golf course that developers had been dreaming about for 40 years. He hired renowned golf course architect Pete Dye to create a state-of-the-art course for a reported cost of $11 million. Once again, the antebellum rice fields-turned lettuce fields had been reclaimed, this time as one of the finest golf courses in the south.

In August, 1991, Peter Applebome reported for The New York Times that some of Pharaon’s parties at the Richmond Hill Plantation were just as lavish as his yard decor. “In the 1980s, the rich and famous—Saudi princes, Pakistani financiers, Chinese television stars and American politicians from Alexander Haig to Andrew Young—flocked here to an improbable social whirl that updated the Great Gatsby to the era of Eurodollars, international trade, arms dealers and drug cartels. Mr. Pharaon is said to have booked every limousine from Jacksonville to Charleston for his out-of-town guests, and people remember them roaring down Ford Avenue to the Pharaon mansion.”

While in Richmond Hill, Pharaon set up headquarters for his InterRedec, holding company, in the old rice mill that Henry Ford had converted to a powerhouse and personal laboratory. Ten years after his initial purchase of the plantation, Pharaon was indicted on federal criminal charges of fraud and racketeering relating to the Bank of Credit and Commerce International scandal.

In 1998, yet another group of investors came calling. Sterling Bluff Associates of South Carolina purchased Richmond Hill Plantation and it’s 1,800 acres from InterRedec for a reported $47 million. Sterling Bluff Associates developed the property into a 400-home private sporting community called The Ford Field and River Club.

Today, the Fords’ Richmond Hill residence, often referred to as the “Main House,” is now the crown jewel of The Ford Field and River Club and a true architectural treasure that serves as the heart and soul of the Club. The main living spaces are used for Club meetings, family reunions, and wine dinners. Many brides and grooms have tied the knot under John Harn’s central Live Oak promenade. Clara’s dining room is being enjoyed once again. The wallpaper has been replaced with a similar landscape reflective of Clara’s love of nature and the outdoors.

In 2017, the Pete Dye designed golf course underwent a multi-million dollar restoration under Mr. Dye’s watchful eye. Ford’s yacht basin is an expanded, modern descendant of the original. Guided offshore fishing, a golf clubhouse, sporting clays, stocked lakes, canoeing and kayaking, an equestrian center, a fitness center, a full-service spa, three Har-Tru tennis courts, a second pool, and 10 miles of hiking trails have been added to the property.

Prior to development of The Ford Field and River Club, extensive archaeology was performed which uncovered layers of history. Native Americans, colonial planters, enslaved persons, Civil War soldiers, Henry Ford, and Ghaith Pharaon all left an indelible mark on this historic site.

In 2019, we too are making history—everyday, using and re-using what has been built before our time. Will this be the last chapter of Richmond Hill Plantation? Only time will tell.