Words by Heather T. Grant Photos Contributed by The Family of J.F. Gregory

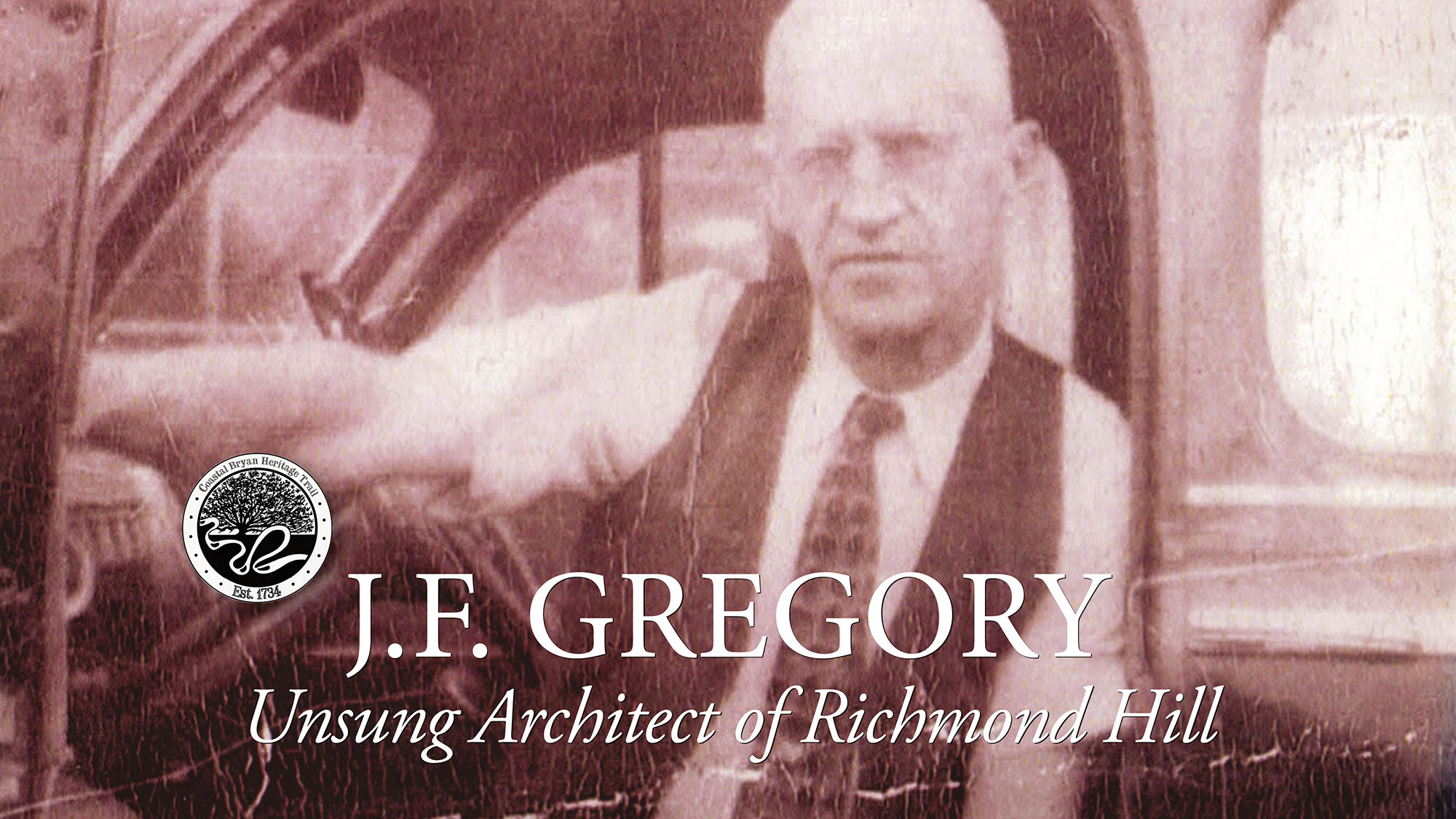

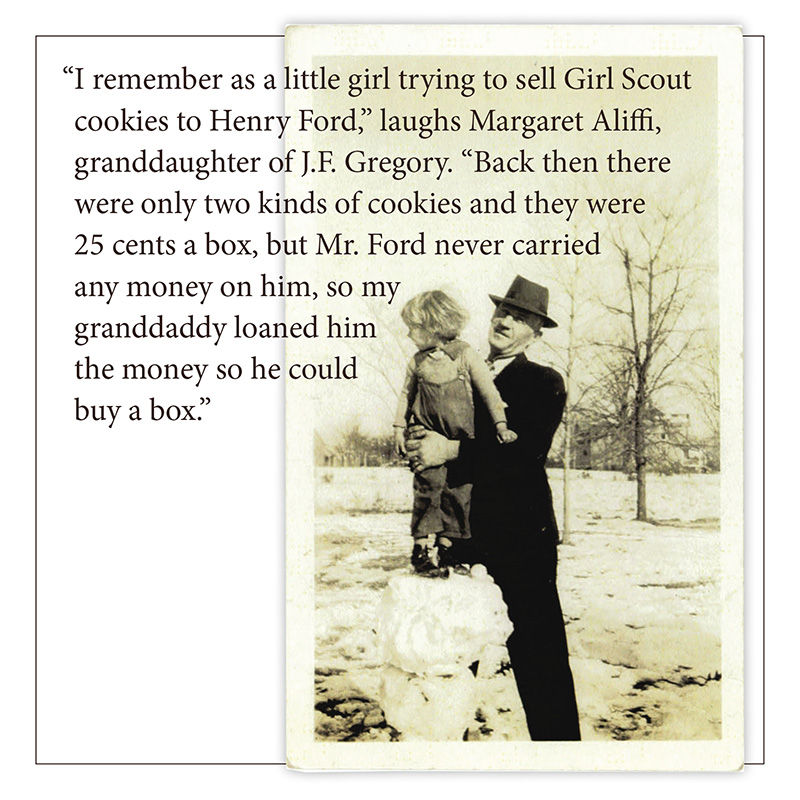

That is just one of the many humorous and heartwarming stories shared about a man known more for the park that bears his name than for his critical role in building the town of Richmond Hill as it exists today.

Jack Fleming Gregory, a son of Charles H. Gregory and Nancy Pete Fleming, was born in Nutbush Township, Warren County, North Carolina, on July 6, 1888. After serving in the Marines, Jack married Dora DeCew Wyckoff and soon moved to the southern part of Georgia with their three young children to work for RJ Reynolds tobacco company. His family had long been involved in tobacco farming and Jack was hired to oversee an experimentation project with the Reynolds Company. “I can see him now,” recalls Margaret, looking off in the distance as if he is standing before her. “He was a smoker, but he always had his signature filter. He knew what tobacco could do to your lungs even then.”

In 1919, after his work in tobacco ended, Jack and his wife Dora moved to Richmond Hill when he took a job at the Hilton-Dodge Sawmill in Kilkenny. While at the mill, Jack worked for the Gignilliat Surveyors and came to know the Gignilliant’s themselves. They just so happened to be good friends of a fellow Richmond Hill newcomer by the name of Henry Ford. With the Gignilliant’s recommendation, Ford hired Jack to be the superintendent of his expanding work in the area.

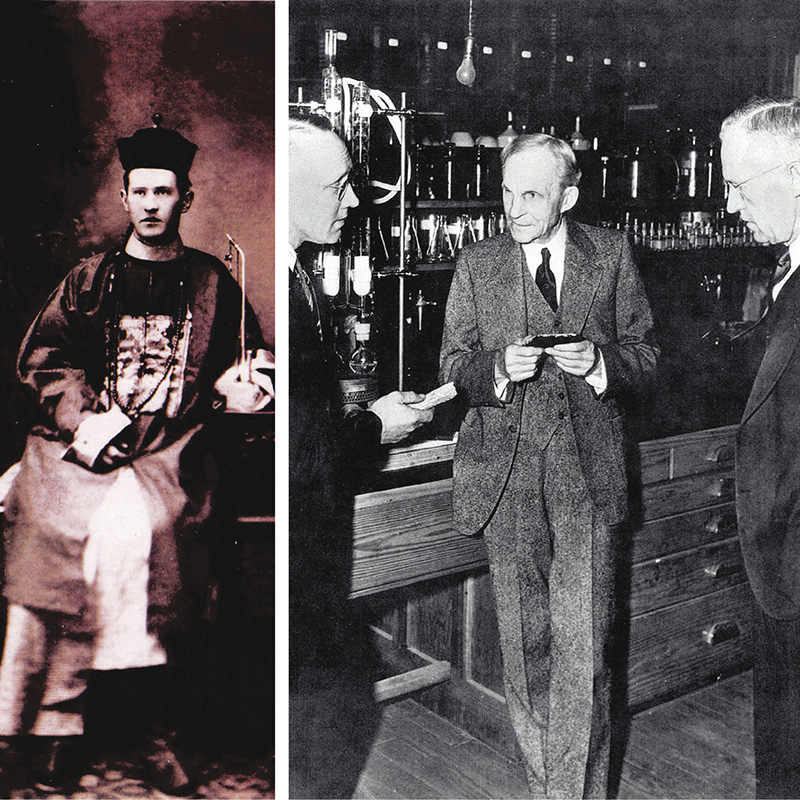

“In a lot of the photos taken of Mr. Ford you’ll see granddaddy standing there next to him,” notes Skee, Margaret’s sister, pointing to a black-and-white photo of the two standing with a chemist who also worked for Ford. “He was responsible for all the workers in construction, the sawmill, all of it, because Mr. Ford wasn’t here very often, so granddaddy was the one left in charge.”

It is easy to overlook the influences of Ford, and his right-hand man, J.F. Gregory, beyond the obvious gated neighborhood and park that are known by their respective names. But as the granddaughters share their memories, the old Richmond Hill came to life as vividly as if it were yesterday.

J.F. Gregory’s home is still standing, occupied by the planning and zoning commission just across from City Hall. “We used to love visiting granddaddy there. The driveway started about where Plantation Lumber is now, and took us down a winding path lined with pecan trees all the way back to that house,” recalls Margaret. “He would fish in the pond and farm the land; it was beautiful.”

Skee describes the fences that Ford, with the help of J.F. Gregory, constructed along Highway 144. “They were adorned with Cherokee Roses and always pristinely maintained,” she notes. The granddaughters recall when every home in The Bottom had an oak tree planted in the front corner under the supervision of none other than their grandfather. “I remember Mr. Ford used to say that people should do what they can to help others—and that’s exactly what he and granddaddy did,” says Margaret.

On September 29, 1960 at the age of 72, J.F. Gregory passed away from stomach cancer. In the late 1990s, Gregory’s granddaughters heard the city was considering names for the parkland just behind their grandfather’s former home. “He was always the quiet man, content to be in the shadow of Mr. Ford, but without granddaddy, there would be no Richmond Hill,” Skee says. In October 1998, the park was officially dedicated in their grandfather’s name. “He would have never believed that his backyard would be a community park,” exclaims Margaret. “Much less the park named after him,” Skee chimes in- as the two laugh just thinking of their grandfather’s reaction to such news.